Emotions and middle school are such an awful combination–for parents and kids. W had the bulk of her frustrations at the beginning of this year. Understanding social drama is hard at this age. I looked online for resources for middle school girls and emotions, and not only did books come up for parents, but there were dozens of resources for middle school girls. I ordered three books from the American Girl Smart Girl’s Guide series: A Smart Girl’s Guide to Knowing What to Say, A Smart Girls Guide Drama, Rumors, and Secrets, and A Smart Girls’ Guide Friendship Troubles. I was SO impressed with all of them. “How to compromise with your parents and teachers. What to do if you need to say no. Dealing with difficult adults. What to do if a friend lets you down. What to say when your friend’s parents get divorced.” That’s just a small fraction of the topics covered in the Knowing What to Say book. We read some of it together, and then she read the rest of them on her own.

W gobbled all of them up in a day.

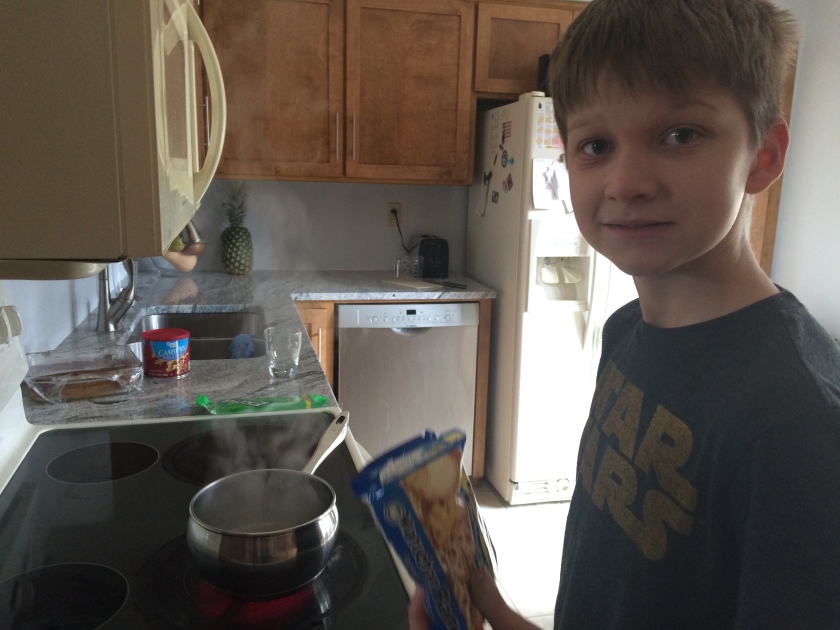

J’s been consistently the one who has been struggling with middle school (and autism) emotions the most. Thursday W had a violin performance at the high school and needed to be dropped off at 6. I was still finishing off the second coat of paint in the kitchen at 5 and sent Steve to grab a Little Caesar’s pizza (because dinner was not happening that night). Just as Steve headed out the door, J yelled, “we’re getting bread sticks, right? RIGHT? RIGHT?”

Steve, in a hurry (and just as stressed as I was) just had pizza on his mind and said, “No, not tonight,” and closed the door.

J came running into the kitchen in full-fledged meltdown, “NO, NO, we HAVE to get bread sticks. I want bread sticks. I WANT BREAD STICKS!”

I’m not sure if it was anxiety because we always get bread sticks, or just plain old selfishness because he wanted bread sticks, but I knew we had a problem because he doesn’t handle either of those things very well. I came down from the step stool, paint brush still in my hand, with an open paint tray in the middle of the floor, and as calmly and quietly (I’m really trying to work on my “you’re driving me crazy/your tantrum is sending my blood pressure through the roof” reaction of not yelling back) said, “J, there is wet paint on the walls, and there’s paint on the floor. Please get out of the kitchen.”

But when J is in full-fledged meltdown mode, and when he’s at that place he wants to engage you in your space and pick a fight.

“Dad’s getting bread sticks, right? Right?” And then immediately came the baiting.

“What happens if dad doesn’t get bread sticks?”

“You can handle it,” I said, because that’s the line we always give J when he’s having a hard time with something. I should have said nothing. I know better than to engage him verbally, because that’s exactly what he wants me to do. It seems really strange, actually, coming from a kid who has been in speech therapy pretty much all his life and has a hard time with meaningful communication and yet when it comes to a verbal fight, he’s all in.

But I was tired, and starving, and I had paint all over my hands and in my hair, and on my clothes and I just wanted to be done with the kitchen and the concert and the night in general. And J was beyond the point of reason.

“You need to go to your room now. You can’t have a tantrum in front of me right now. There’s paint everywhere. You have to go to your room.”

“I’m not having pizza. I’m having bread sticks AND pizza. Not just pizza, bread sticks AND pizza,” he kept repeating. But after about a minute of crying and yelling, he stomped up to his room. And cried and screamed for about 5 more minutes, came back down again with big red puffy eyes (really puffy because he’s battling eczema around his eyes right now too).

“I’m going to have leftovers.” He announced.

“Wow. Yes,” I said. “Good idea to solve your problem.”

By the time Steve came home with the pizza, J warmed up his leftovers in the microwave. And ate 3 slices of pizza.

The optimist in me thought we’d be past the meltdown and tantrums at 13. But we’re still here. The good news is that, as crazy as the bread stick story sounds, his meltdowns have come a long, LONG, way. Just a year or two ago, we’d be engaged in this battle for at least 45 minutes. After 45 minutes, he would still be inconsolable. Steve would probably be headed back to Little Caesars to get a package of bread sticks. One of us would be missing the concert because J wouldn’t be able to pull himself together by then, even with winning the bread stick battle.

Helping J manage his emotions and deal with them in an appropriate way has been a struggle for as long as I can remember. In fact, that’s one of the main reasons he still is in speech therapy. J doesn’t have a stutter, lisp, or struggle with pronunciation. He struggles with meaningful communication, social appropriateness, and understanding other people’s point of view, and I owe a lot of J’s progress to J’s speech therapists. They create social stories to help him navigate stressful situations, they create social stories to help him know what to say. He has a class with other kids on the spectrum, other special ed kids, who also need to practice their speech and social skills. Sort of like W’s Smart girl books. A little more simplified.

There are no Smart Boy’s Books out there to help boys understand and navigate their emotions. (If there are any, PLEASE let me know). Most of the books under “middle school+boys+emotions” are parenting books, or books that are gender neutral in approaching emotions and social struggles. There are very few middle school boys books geared to the boys themselves that go beyond the puberty talk. As I’ve looked through books that might help J navigate the social emotional issues he will facing in the next five years and beyond, I’m finding that it’s really hard to find these books about boys for boys unless you are a boy on the spectrum. Books for kids on the spectrum are good, but I want him to see that other boys struggle and have questions about their emotions too.

J needs empathy, kindness, social appropriateness, and managing emotions spelled out for him. And I’m guessing he’s not the only boy out there. I’m guessing there are non autistic/spectrum boys who need some guidance in these areas too.

It’s actually one of the weird things about autism I’m really grateful for (not the tantrums), the weekly discussions on feelings, the instruction he gets from his speech therapist and psychologist. I feel like boys don’t get much instruction on how to navigate their emotions. It’s strange to me that we think that young girls are the ones who really need direction in this area or are the only ones who want to explore and talk about these things. Clearly boys struggle to understand their emotions and social worlds too.

J loves talking about emotions. He loves trying to understand other people, even when it’s hard for him. That’s why he’s always loved speech. And he gets excited to visit with his psychologist Dr. T.

And that’s why I’ve started reading , with W’s permission, A Smart Girl’s Guide to Knowing What to Say with J. Some of it is still a little “old for him” but I’m keeping that book on my radar. In fact, I’ve picked out some pages he can work on right now. Like “25 things to say after hi.”

So far, he’s into it. He doesn’t even care that it’s “for girls.”