To say that J has a volatile relationship with numbers would be an understatement. J and numbers have a long and complicated history. Numbers were among the first words J picked up in the early years while we were still struggling with speech. J could pick out numbers patterns and knew most of his single digit subtraction and addition facts pre-K. J had an obsession with numbers. He loved numbers. But at around grade 1 / grade 2, he started to develop strange fears about numbers.

He’s been living with number phobias ever since. The ones J deems “tainted” or “threatening” change every few months. Right now, one of those numbers just happens to be 142.

J also just happens to keep track (and numbers) every single day of the school year. That way he can keep track of every single catastrophic event (in J’s eyes, anything that happens unexpectedly is a catastrophic event) and which day (aka NUMBER) it happens on. My theory is that’s how some of the number phobia starts. It at least explains a piece of it.

J has been dreading the 142 day of school for about a month now. I made an appointment weeks ago with Dr. T, J’s therapist, and they talked about strategies he could use to get through the day when it came around.

I used the Social Thinking Language that J’s speech teachers have really been trying to enforce over the last few years, the idea of big problem (near crisis) vs little problem (a glitch).

J (and a lot of kids on the spectrum) have a hard time figuring out that most things in life fall on a spectrum. I think this has to do a lot with the faulty switches in their brain that are rooted in anxiety. To them, either something’s a threat, or it’s safe. Either something’s good or it’s bad. It’s that cave man protective skill. J’s brain can’t slow down enough (naturally) to think that there might be different and varied approaches to looking at the world. Or that most things we see every day aren’t big problems (we don’t get earthquakes or tsunamis every day). Most things are little problems, like a “glitch” (running out of milk, getting corn stuck in your teeth, you know, annoying, but not life-threatening). There’s a great link for the Social Thinking chart explaining glitches here.

Up until the last year or so, all problems=big problems.

Will all of that positive narrative we had been building the last month, I felt J and I were ready to face this week. J was feeling confident in his anxiety strategies for handling the “bad number.” Then Monday came, four days before D-day, and I wasn’t sure we were even going to make it to the anticipated apocalypse.

It started with Monday morning drop off. Monday was French Fry Day (another phobia for J—he’s deathly afraid of French fries) and so Steve had packed a bag lunch for J the night before. For the first time in a very long time, we were ON TIME. I wanted a great start to the week, especially with 142 coming up, and we were off to that great start, until I drove up to the school and J asked, “Where’s my bag lunch?”

Crap! I thought. “I’ll bring it sometime this morning,” I said. My mind immediately started spinning on how I was going to pull this off. Would I have to be late/cancel my 9:00 am appointment? I’d have a little time to squeeze after. But would it be enough time before lunch? Would he be a hot mess of anxiety all morning long until it got there?

“When?” J insisted “When are you going to bring it?”

“Sometime before lunch.” I said, because I was still trying to figure out the logistics in my head.

“When before lunch?” I could see the anxiety stewing already. The shaking in his hands. The way he nods his head emphatically, demanding an answer.

I let W out of the car and watched her dash into the school. “Okay, we’ll drive back home now, and you’ll be a few minutes late.”

J hates being late, but I think the prospect of confronting a tray of fries in the lunch line and French fry anxiety trumped the being late anxiety. We got home, got his lunch, and got to school. Forgotten lunch, just a little problem—a glitch. Something I needed to remember too.

Shortly before pickup, I received a text from J’s para that I might want to pick up J early. His shoelace got caught in the pedal of the stationary bike he uses daily for a brain break, and he got into a small panic attack because he couldn’t get his foot unstuck momentarily, but it was enough of problem that it took him a good five minutes to calm down after it happened. But by the time I got there, he had pulled himself together and was pretty proud of himself for doing it. Again, small problems—a glitch.

During track practice after school, there was a mix-up on the 4 mile route. The pack J was running with turned around about the 3.5 mile point. J didn’t know where he was going, and so he turned around with them. But, by the time the coach and I caught up to them, the coach told them that they had to run all the way to the gas/station and stop sign. J was LIVID. J didn’t want to turn around run and head back for the additional ½ mile or so and then turn around again to go back to the school. His mind was fixed on the return trip. He told me he hated me, and then he told me all the things he hated about everything else in the world, and 142 came up again—all during the run back for a good mile. Finally I said, “That’s enough. If you make it to the school without complaining, that means you will have handled 2 glitches today. The shoelace glitch AND the route mix up.”

For some reason that clicked with him. And he made it back, without a peep.

Monday was crazy and full of glitches but I really think it helped us prepare for the bigger anxiety a few days later. Monday J was able to work through all the small problems that came his way, which gave him the confidence to use his coping skills and handle 142 in the way he needed to. And he did.

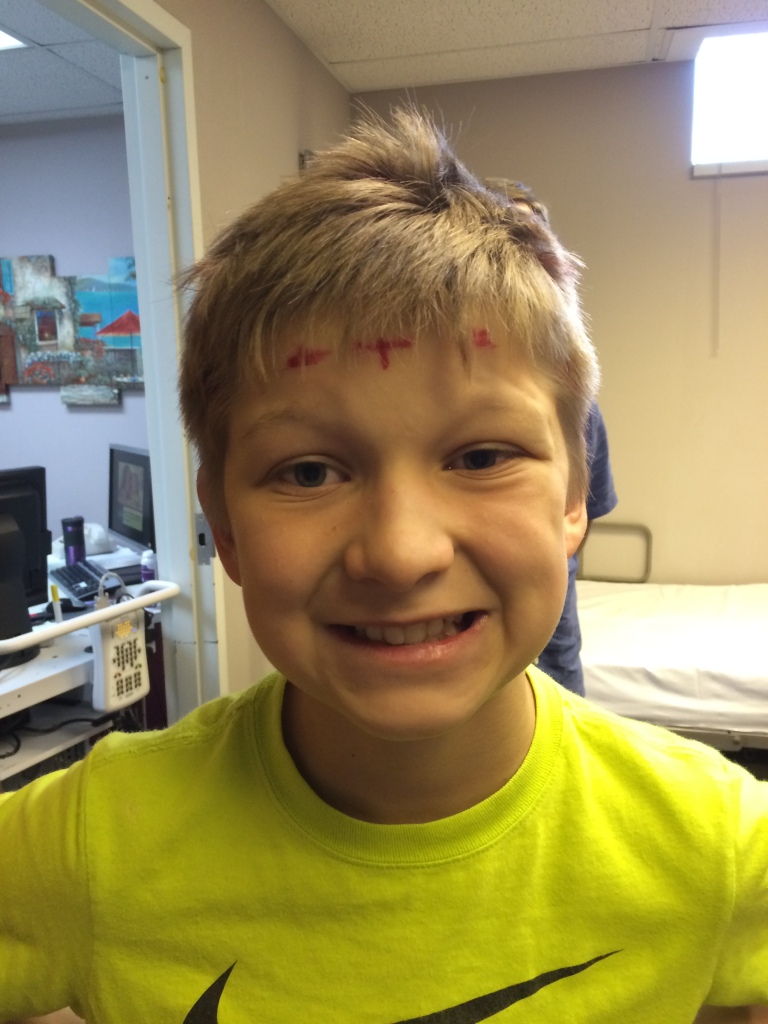

Thursday came and we made it through the 142 day of school with no problems! Even with speech cancelled that day (J hates it when people mess with the schedule) He had made it! He got ice cream at DQ for handling it, just like we promised him last month when the infamous 142 started showing up in J’s daily conversations. With J, food always works well as an extra motivator.

“142 isn’t a monster,” J explained to me Thursday night. “It’s just a number” he said shrugging. “Just a glitch. It comes and goes. It won’t last forever.”

And just like that, 142 came and went without incident. Not a problem at all.