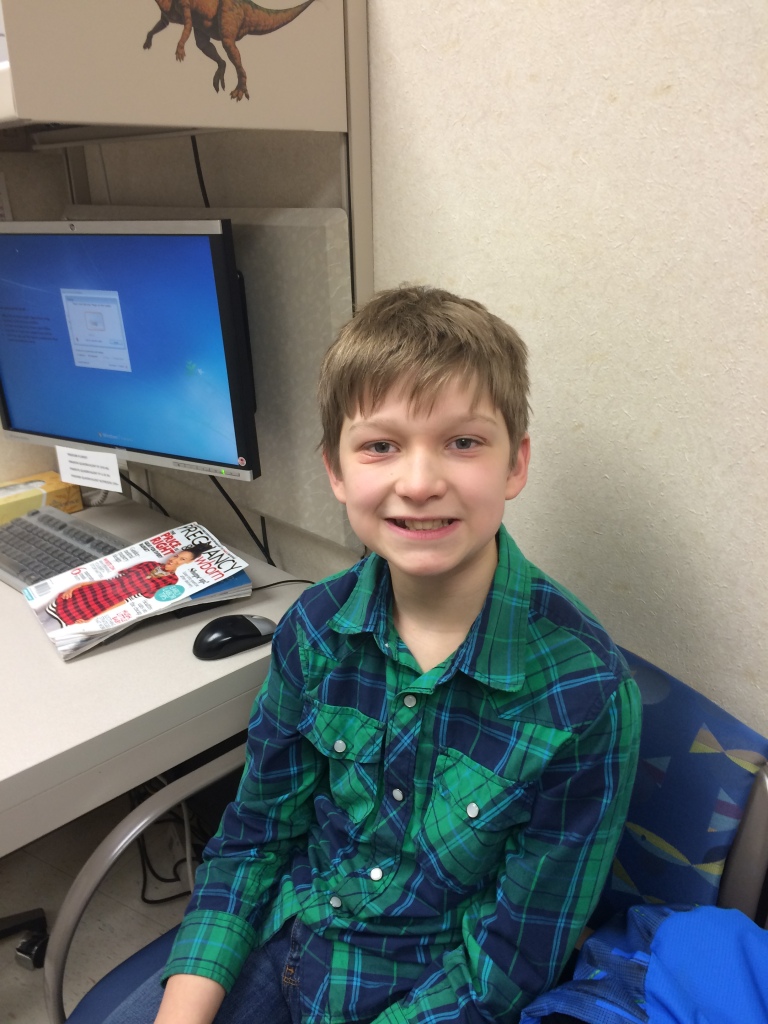

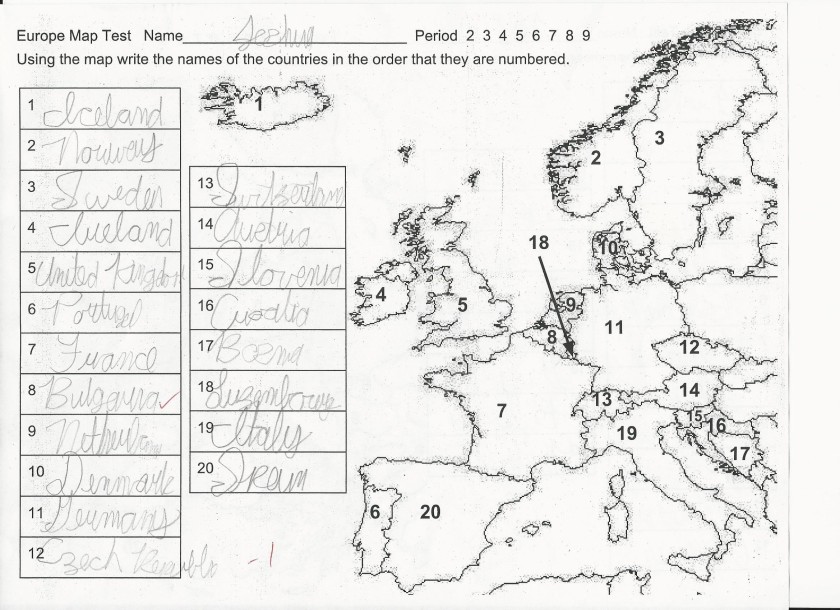

I have a world map and a map of the US folded and stacked on top of my jeans in my closet. J’s framed Imagine Dragons poster is also in our room, leaned up against the foot of our bed. They’ll be there until Tuesday, fingers crossed, until J earns the right to have them back.

Right now when I get dressed or go to bed, I have these visual reminders of how much space J can take up in my life. It’s easy to let J overtake every aspect of my life. Space is something I have to fight for. It doesn’t just happen.

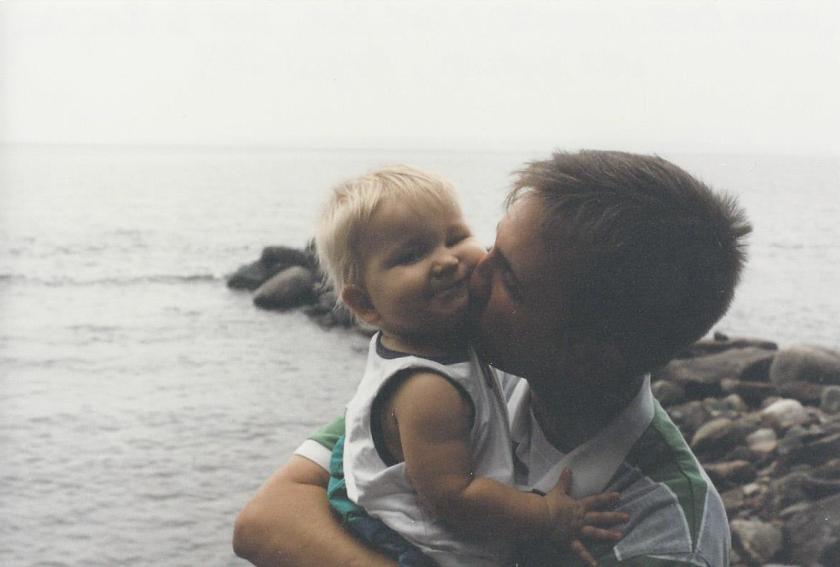

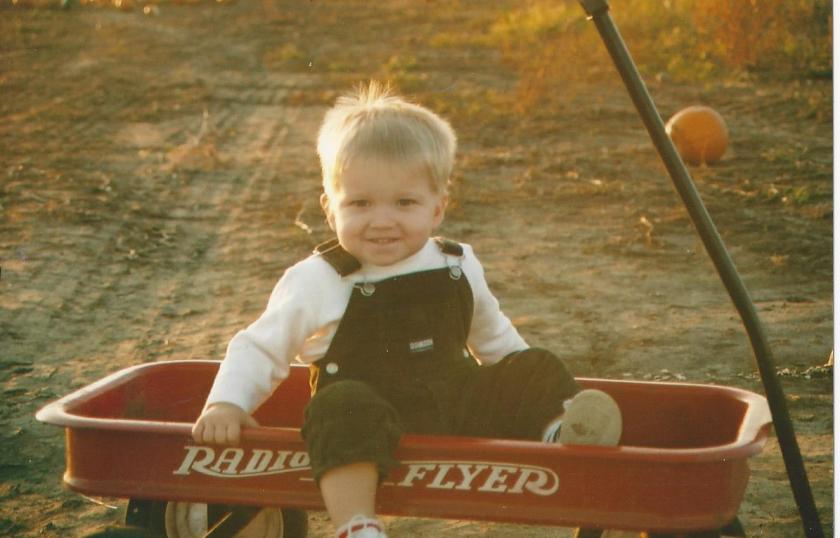

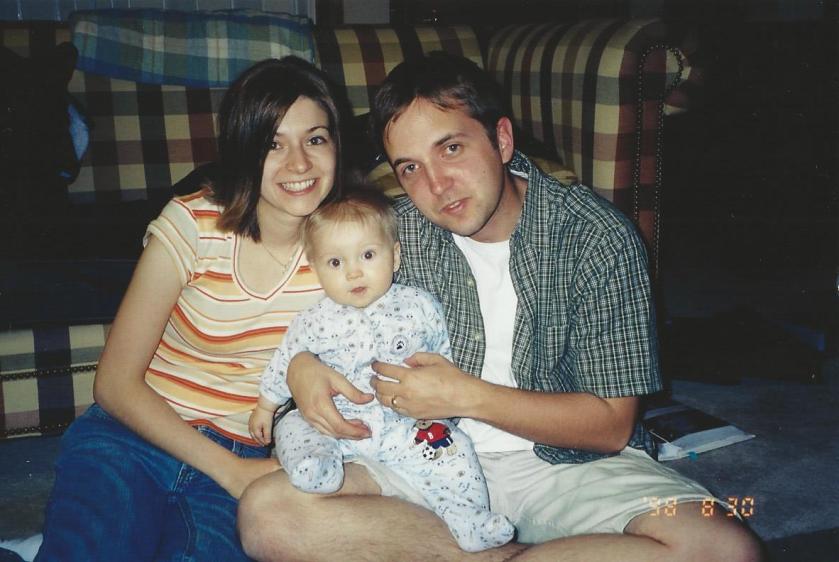

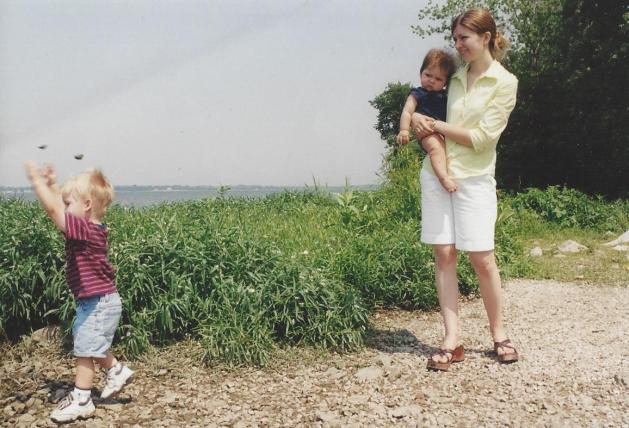

I got married young (just shy of 21). I had J less than a week before turning 22. J and autism have been my entire adult life. Maybe that’s why I fight so hard to make sure I have my space without him.

It’s easy to become an autism martyr. It’s easy for autism to creep into every thought you have. It’s an easy go-to place to wallow in when you feel like your life’s not going the way you want it to. That’s why it’s so important that I fight for my space, because it’s the only thing that keeps me sane through this whole thing. I still have my life to live.

I was “me” before Steve, J, or W. I’m still that person (yes, evolved a million times over from the experiences I’ve had over the past 15 years married with kids) and I’m always trying to make sure I learn and improve on that person too. It’s important to my family, I feel especially to my daughter. She needs to feel the right to develop herself in the ways she needs to as well–unlike me, her life started with autism. Even though I love my children, I’m not just their mother. I am so many other things too. It’s dangerous to get stuck into seeing yourself as one thing, especially a mother of an autistic child, because you can’t see the myriad other things you are too.

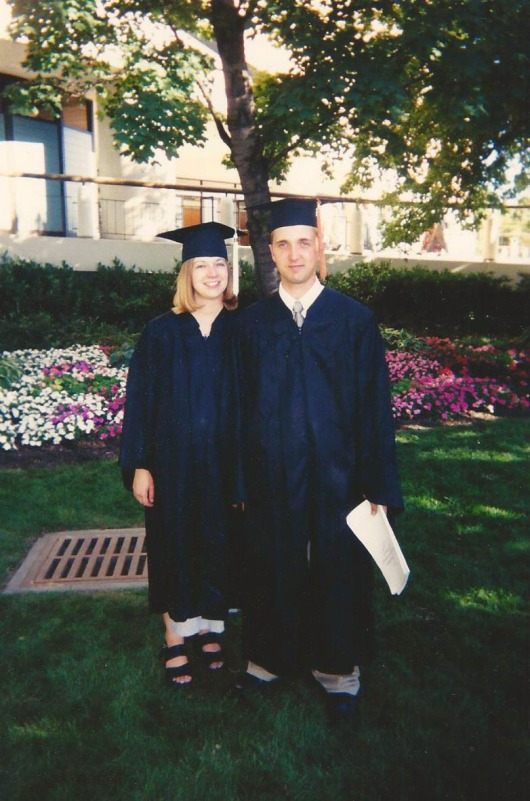

It’s hard to say if I’d feel the same way or not if J didn’t have autism, although I’m guessing I probably would. I’ve needed that “me” time before we knew J had autism. We were a poor grad school family when Steve was attending the University of Illinois and I substitute taught in the Urbana school district every Friday, while pregnant with W. The extra money was nice, but getting out of the house once a week, being an adult “me” was worth much more than the money. Raising another human is an especially exhausting, all-consuming experience. I had to step out of that, even for a short amount of time, on a regular basis.

When W started kindergarten, I really felt I needed to go back to school again. With a lot of Steve’s support (he took a sabbatical during some of that time so I could TA and go to school full time) I was able to graduate with my MFA. I had gone back and forth between speech therapy (or some other education emphasis) and an MFA. Speech therapy (and even education) required that I go back and take more undergraduate classes before a masters program. My life track before marriage and kids was in English, so the MFA won out. A few weeks into the program I realized how important it really was that I develop “me” in other ways than in the special needs department and that I was really starving to develop my own interests.

Over the years I’ve realized that in all the ways I fought for my space, I’ve ended up reciprocating them back to J and my family. My experiences in the Urbana Public School District helped me understand the special education process better, even when I didn’t have a stake yet in special education. I could see teacher’s perspectives and how challenging their jobs could be. I’ve been able to see hundreds of kids with different backgrounds, different learning challenges, and different learning strengths that have helped me understand my kids better.

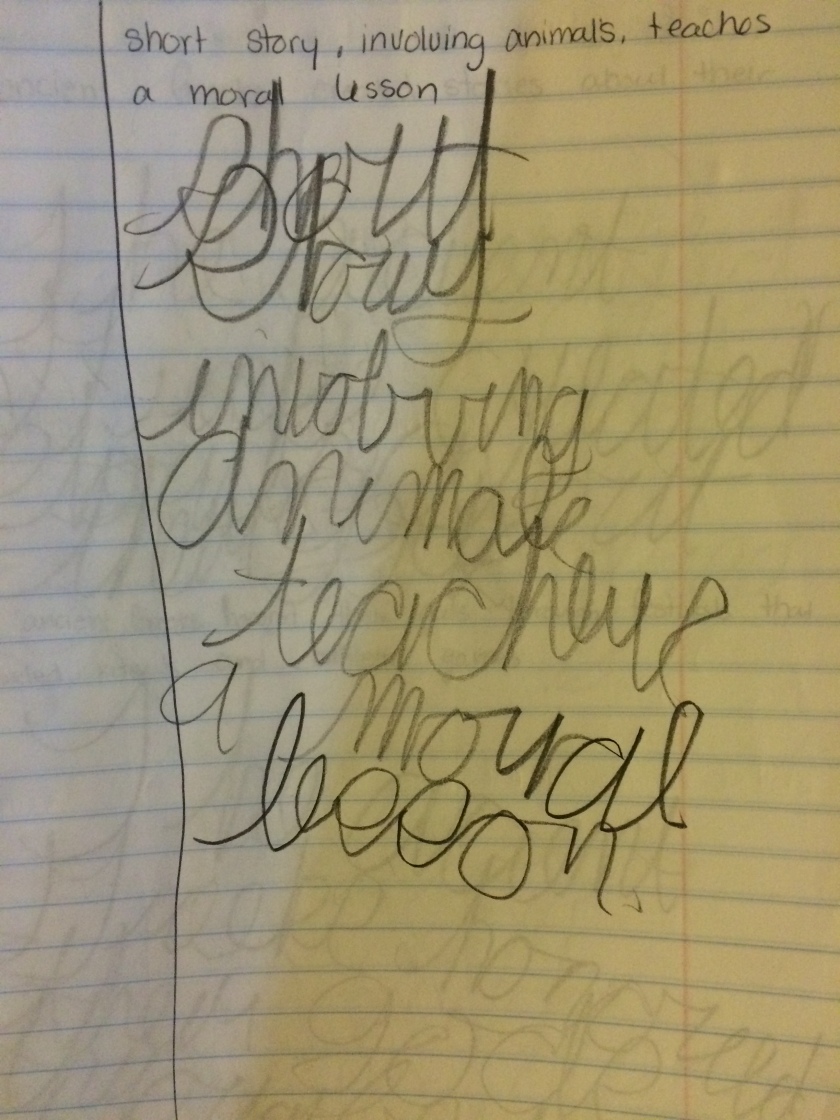

My MFA experiences have been invaluable too. I use one of my favorite reading comprehension strategies taught in my TA class with J on a daily basis. Understanding the human experience and exploring human motivation has helped me imagine a little better what J’s world probably looks like. My creative nonfiction class changed my whole perspective on what reality means to each person, and how even two people sharing the same experience will tell their stories in very different ways because of how they interpret the world around them. Creating fictional stories outside of my experience helps me understand others better and has helped lessen the pain of well-meaning, yet hurtful comments I’ve received. It’s helped me escape my life in healthy ways when I need to the most.

I try my best to read my family’s cues to make sure there’s a balance. Sometimes you get stuck temporarily and a balance can’t be reached, and things are just hard for a while. Even though both my kids were in school, I know the last few months of my MFA were hard on W. I spent many late nights on thesis revisions, I’d grade papers after school or cram reading assignments in while my kids played outside. I’d set dinner out for the family, or Steve would make something, and I’d head out for night classes and workshops. It was something everyone in our family had to make adjustments for. Right now our family is changing again. J needs special attention sometimes with the ups and downs of middle school, and W has her own share of challenges too. Sometimes I have to put off my own projects temporarily for them. But it’s okay, because we all have the right to be needy sometimes. There’s a lot of give and take that happens here.

I know every family, every relationship, requires negotiation of space. It’s a dance that needs to be monitored constantly. Sometimes I’m better at managing that dance than others. Sometimes I play the autism martyr supermom and forget to take care of myself and sometimes I play the selfish, self-pitying mom and forget that sometimes I need to wait my turn too–family issues function on a triage system. I think the most helpful revelation for me through all of this is that our family is made up of constant, fluid seasons of need. Everyone in our family should have a turn to have their needs met, especially when autism is constantly monopolizing that space.