The turn of events this week are all because of one teeny tiny mistake. I thought J would picture this week in the exact same way as I pictured this week. I do this sometimes. I remove me and J from the world for a little bit, we work hard on hard things together, and then I expect us to end up at some better place I’ve created in my mind. I’m not shooting for the stars or anything. Just a small, positive change. One step forward instead of three steps back. That’s all. No Disney inspirational movie making plot here. I’m just looking for baby step progress.

This is how I saw this week and the events leading up to it:

We run all winter. We master the mental and physical hoops that come with running in below freezing temperatures. Track season starts. J runs with the group without complaining—with that new mental capacity we’ve been practicing the last five months. He stays close enough to the group, maybe a block, or block and a half behind. Last of the pack, that’s what I’m anticipating. But not too far behind. Not four or five blocks behind like XC season. That’s how I saw track happening. Like I said. I wasn’t expecting anything much or outrageous.

This is how J saw this week :

Just like XC. Same routes, same friends, same coaches. Because that’s what I told him it would be like. “Track is just like XC, J” I had told him over and over again for the last 5 months. “You’re going to love it.”

And that’s where I made my mistake. J took me literally. He thought track would be the literal version of XC reincarnated.

And boom. Worlds collided. His expectations vs my expectations and you have full on catastrophe.

That’s what started Monday’s troubles.

Monday I get a call from one of J’s paras around 2 in the afternoon, letting me know that the first track practice will be held in the cafeteria after school (because of weather) and so we could discuss where I could meet up with them. “Oh,” I said. “We should probably let J know then. I think he’s expecting to start practice up at the high school.”

J’s para text a few minutes later:

“I told j that track will be in the cafeteria today and he did not like that idea.”

No, he did not like that idea at all. When I came to meet him after school, he came out with his track bag over his shoulder, fully dressed in the clothes I sent him to school with.

“He had a little meltdown—not a big one where I had to call the principal—but he said he didn’t want to go to track today. He says that he doesn’t want to go to the cafeteria for track.”

On the way home, J was all tears when I asked him about why he didn’t want to go. I had my suspicions. In J’s brain kids shouldn’t be running in the cafeteria—or the halls of the school—which was where they were going to practice sprints. In J’s brain, that’s not what track looked like. Track was going to be just like XC. Running for a long time. At the high school. Outside. With friends. Just like I had promised.

“How do you feel?” he asked mid-mini-meltdown in the back seat.

“Sad. Disappointed,” I said. “I thought you wanted to run track.”

When we pulled into the driveway, J suddenly stopped crying. “I want to go back,” he said determined. “I WANT to go back.”

J changed quickly and we rushed back to the school. He joined the track team in the cafeteria. I watched him as he fully participated with his uncoordinated body, arms and legs flopping all over the place as he tried the lunges and skips and jumps and other form drills with dozens of other kids in the tiny cafeteria. He also waited patiently for all the boys to run sprints on the 3rd floor hallway.

“J, I’m so proud of you,” I said on the second drive home. “Isn’t track great?”

“Yes! I’m going to do it again tomorrow.”

“Wow,” I thought. “We’ve done it! J got over the changes. He’s adjusted his expectations. It was just a little glitch, but now we’re good.

And then Tuesday happened.

Around two in the afternoon I got another call. J had another meltdown and this time principals were involved. I have to say, sometimes when I get called in, it feels like I’m the specialist called into a crime scene—like Sherlock Holmes, the person who finds the clues that no one else sees and has to figure out what the heck just happened. We get J calmed down and settled, and we try to figure out what happened. They tell me J started obsessing and stressing out about numbers, and words, and spellings (all symptoms of his anxiety) and then it just escalated from there. But the thing that sticks out to me the most is the phrase J keeps saying over and over in the room, “I don’t want to stay after school.”

And that’s when my best educated guess clicked—I say educated guess because by this point, I know I will never truly understand the reasoning and logic that happens in J’s brain.

“I think he’s stressed out about track,” I said. “He had a mini meltdown after school about it yesterday, but we went back and he ended up being okay. But maybe he’s not okay. I mean, it’s not what he’s expecting—running in the school, for one thing.”

And then I remembered something else.

“In elementary school, if J had a bad behavior day, he had to stay after school—like detention. I think he’s equating staying inside the school, after school, with detention, even if it’s for track.”

J came home early with me. He missed track. As I drove W to piano lessons, we passed the long distance track team running. Outside. I was all tears. Because J has taken 4 minutes off of his mile time over the winter. 4 whole minutes. And because of his anxiety—the most disabling part of his autism diagnosis, he wouldn’t be able to run track. I started questioning if XC was going to be a reality in the fall. We came home and I made a T chart comparing XC and Track for J. J wrote down his “new picture of track looked like.” I explained to him that staying after school for track was not detention and that we didn’t do detentions anymore. And then I was done parenting for the day.

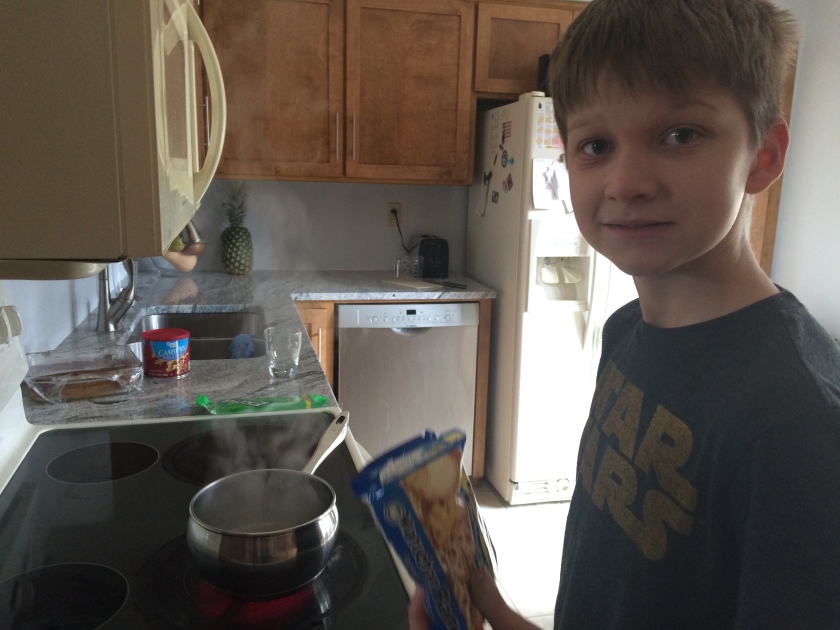

I asked Steve to do all the homework with him that night. I made dinner and read a chapter of The Roundhouse. Steve and I watched Netflix the rest of the night.

And then came Wednesday

By Wednesday, I had no expectations for anything. J saw the kids on Tuesday and said he really, really wanted to try track again. The paras and I texted back and forth that day about it. They said J was excited to do it. I met him after school. J’s special ed teacher (who is also one of the track coaches) let me know that the middle school long distance team would be meeting at the high school (not because of J, just because that was the plan) and so J and I met the team at the high school. And J ran with the boys/girls high schoolers and middle schoolers, straggling about a block behind the last girl runner. This is what I was thinking track would be like. It was a good day.

Thursday practice looked much like Wednesday’s, except the boys and girls middle schoolers ran their own route. J was able to keep up with at least one other runner at all times during the run (which is a huge relief for me, having a buddy who can also be aware when crossing streets). He even finished his run with the first finishing girl.

I look back at this week and I think, “Wow, that’s not how I expected this week to go at all—after Monday. Especially after Tuesday.”

I think that’s what keeps me going. It’s what keeps me from giving up altogether with J. Knowing every day will be so much different than the day before. It’s so unpredictable, that even after a bad day I can’t guarantee that the next day will be bad. Living with J is truly full catastrophe living.

Jon Kabat-Zinn once said that “the nature of the human condition [is] to actually, at times, encounter uncertainty, stress, pain, loss, grief, sadness and also a tremendous potential for joy, connection, love, affiliation. And all of that is ‘the full catastrophe.’ It’s not just the bad stuff. It’s everything. And the question is, “Can we love it, can we live inside of it in ways that actually enliven us and allow us to be fully human?”

That, says Jon Kabat-Zinn, is what full catastrophe living is. And I think that’s the perfect definition of this whole parenting business.

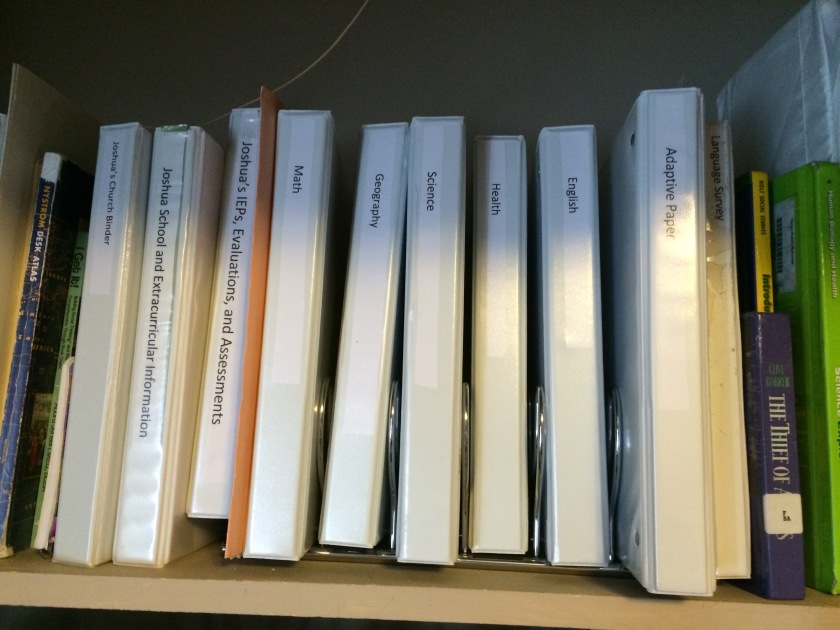

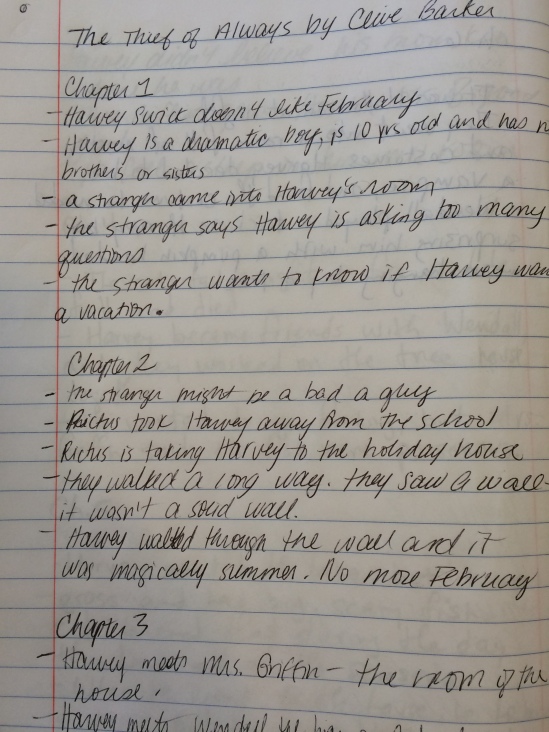

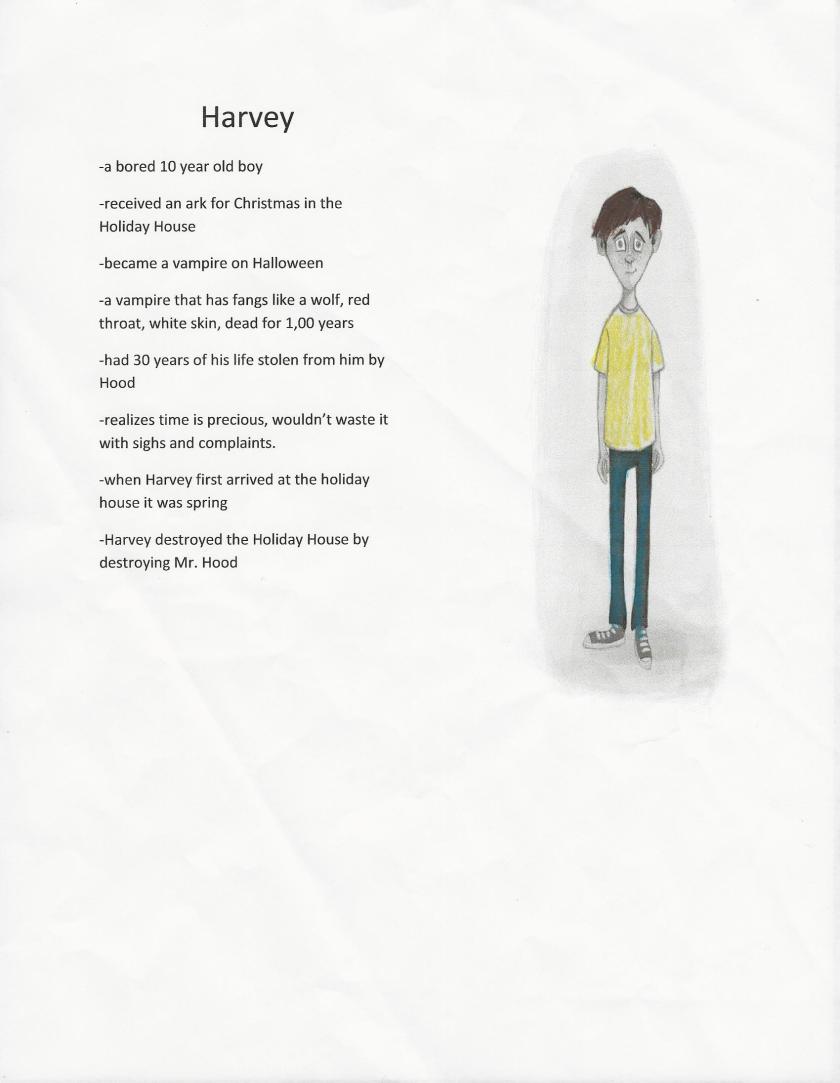

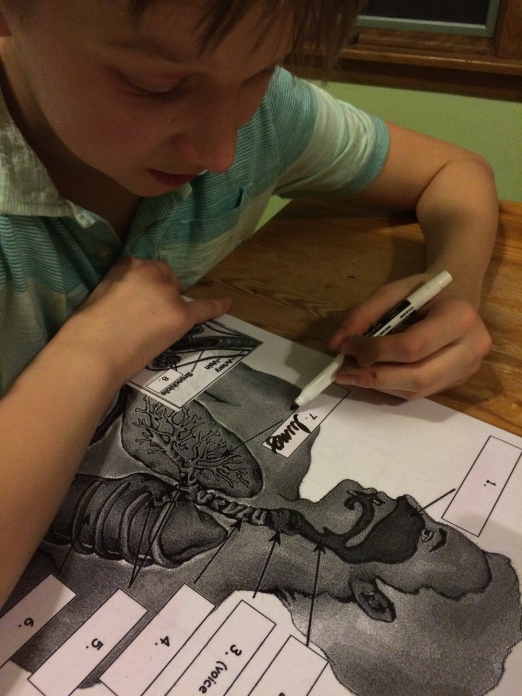

It’s taken the second semester of grade 7 to feel like I’m finally understanding how to reinforce what J’s learning at school at home. I feel like we’re starting to get a good system going with J’s paras and teachers in how to modify assignments, tests, and practice assignments that will help J learn the best.

It’s taken the second semester of grade 7 to feel like I’m finally understanding how to reinforce what J’s learning at school at home. I feel like we’re starting to get a good system going with J’s paras and teachers in how to modify assignments, tests, and practice assignments that will help J learn the best.